Antarctic Cascading Ice Flow…Globalwarming Effect

Advice and Guide, Interesting Stuff

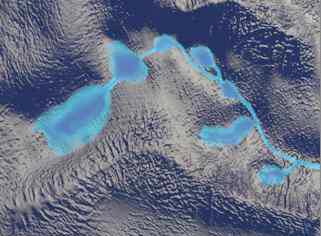

An image from a NASA animation reveals the possible arrangement of the large network of lakes scientists have found deep beneath an Antarctic ice flow.

The waterways help carry ice from Antarctica’s center to the sea, in a finding that may clarify how global warming will affect the world’s ocean levels

A series of connected lakes has been discovered deep beneath glaciers in Antarctica and are speeding streams of polar ice into the sea, scientists announced yesterday.

The lakes appear to be filling and emptying rapidly as water cascades from one lake to another before eventually reaching the ocean.

The find is important, because scientists believe this water below the surface helps carry ice into the sea, ultimately contributing to a rise in sea levels.

“It acts as a lubricant, greasing the skids of the glacier’s movement,” one of the study authors, Robert Bindschadler of NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, said yesterday at a press conference in San Francisco.

The team’s finding, which may help scientists better understand how global warming will affect the world’s ocean levels, appears in today’s issue of the journal Science.

Jumping Ice

Scientists discovered the lakes using a satellite that was tracking changes in the elevation of Antarctic ice over three years.

Even though the ice is hundreds to thousands of feet thick, it still floats on the underlying water, rising and falling as the lakes fill and drain, explained the study’s lead author, Helen Fricker of Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, California.

Fricker said her team was surprised by the fluctuations they witnessed in such massive sheets of ice. In one instance, a 135-square-mile (350-square-kilometer) section of a glacier dropped 30 feet (9 meters) between October 2003 and November 2005.

“That’s about the height of a three-story building,” Fricker said. “We were really amazed.”

Since then, the lake appears to have begun refilling.

Scientists have long known that there are lakes underneath parts of the Antarctic ice. Some 145 have been charted, one as large as Lake Erie.

But this is the first time such lakes have been discovered beneath the streams that carry ice from Antarctica’s interior to the giant, Texas-size Ross Ice Shelf on the ocean’s edge.

These ice streams carry a great deal of ice to the ocean, but the new study didn’t find any unusually high rates of ice loss.

“We can’t predict what this ice stream is going to do based on these measurements,” Bindschadler said.

But, he added, the more we know about Antarctica’s underground plumbing, the better we’ll be able to make predictions in the future about how these ice streams will affect the levels of the world’s oceans.

“This is a major step in that direction.”

May 22nd, 2007 at 2:47 pm

boring

May 29th, 2007 at 2:27 pm

hi i hate this